Christianization, Acculturation and Its Cause in the Mohawk Tribe by Kelly Schassler

In the efforts to convert Native American people to Christianity, groups such as the Jesuits founded missions. While these missionaries' goals were to Christianize the population, and in their belief, save the native peoples' souls—they were also in the process of erasing the culture of the tribe. An account of some late attempts by the correspondents of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge to Christianize the North American Indians, by the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, detailed the spread of Christianity among Mohawks in the 1760s, and the ways that it seemed to be achieved. Another document narrated an encounter with the Mohawk tribe, The Character of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, by Lord Cadwallader Colden, and presents a picture of the declining state of the tribe in 1727, which shows another perspective on why the Mohawk Indians may have been willing to convert to Christianity.

An account of some late attempts, came from the perspective of the missionaries, and gave a look into their process of converting the Mohawk tribe to Christianity. It shows that the Mohawks were involved with Christianity at the time, however, considering the bias of the source there is a possibility that the author decided to omit any religious practices that did not fit in with the authors definition of Christianity, or some Mohawks that may not have accepted the new religion. Throughout the piece, the missionaries stress the Mohawks devoutness. In one instance the essay described a mass at Sabbath, "a very full and attentive assembly, as devout as ever I saw, and properly raised with a well-tempered zeal."[1] the author emphasized the extreme reactions the people had to the sermon, during which, "The whole assembly was moved...some wept and covered their faces."[2]

By describing the Indians' reaction to Christianity, the author tried to prove that Mohawk Indians were easily adopting the religion, and were incredibly taken by it. They further stressed how many were eager to convert and incorporate this new religion into their lives (which would ultimately influence their culture). Some Indians are said to be concerned about their soul, and what they should do in order to be favored by God. Others are already well established in Christianity and are "zealously engaged"[3] in their practices. Did the Mohawk tribes actually lose all of their old customs, as the author would like to indicate? There is an excerpt in the same document that notes how children play a vital role in the process of acculturating the Mohawk tribe. It is explained that they need to set up schools among the villages where the Indian children can learn English teachings so that they may become interpreters, or missionaries themselves.[4] If this process is read into, one may realize that the more the children are being subjected to a different religion, customs, and rituals, the less time they have for their own cultural practices—which may cause them to be phased out entirely.

If the Mohawks adoption of religion wasn't solely due to the desire to be accepted by the Christian God, then what were the other causes? The Character of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, by Lord Cadwallader Colden gives insight on this. Colden explains that the Mohawks were part of The Five Nations, an Iroquois Indian confederacy of New York, comprised of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca tribes, and while he describes the people as barbaric he also points to the fact that many of the tribes were at war with each other. One can infer, that due to war, deaths, and dwindling populations in tribes, that The Five Nations banded together largely in part because they were vulnerable to attack due to these weaknesses.[5] Their practices are as described, "An old Mohawk Sachem, in a poor blanket and dirty shirt, may be seen issuing his orders with as arbitrary authority as a Roman dictator."[6] They are not trying to put the Mohawks in a good light, and their descriptions of them differ greatly from that of the missionaries where they call them devout and well-tempered. In this case, the author wants to demean their authority, he pointed out that it was all arbitrary, that their power wasn't actually substantial. He wanted to portray them as weak, and their state as shabby, by comparing the Mohawks to his own standard of living and expectations. However, despite the negative connotations, this shows how war was a very important practice in the Mohawks culture.

So why did this tribe convert to Christianity, and allow for the missionaries to be built on their land? The answer, in examining the documents, seems more complicated than the missionaries would want one to believe. Due to the fact that the Mohawks became part of The Five Nations, it seems as if they did not have as large of a population as they were used to, as they chose to band together with other tribes instead of continuing on alone like they had in the past. With less numbers, comes less power, and the missionaries would have had an easier time influencing the tribe to join them because of it. If they accepted the missionaries, it brought the Mohawks protection from other tribes, which may have been a deciding factor to allow the missionaries onto their land in the first place.. The missionaries also seemed to start indoctrinating children at a young age to their faith, which meant that it was easier for the religion to take root in the tribe. As a result, new aspects may have been added to what constituted as Mohawk culture, while older ideas could have been forgotten. The sources provide a glimpse of Mohawk life, culture, and religion—though they depict it with heavy bias included. From the missionaries point of view, they portray the Mohawks as zealous, and as the perfect receptacle of Christianity, that they love everything that is happening in order to lead people to believe that they are doing nothing but succeeding in their Christianization of the Indians. By comparison, the other document was biased in that it wanted to show the Mohawks in a negative light, and insinuate that they held no power, and were a poor people. However, by reading into them, one can see that this shift toward Christianity may have occurred, and that numerous factors probably fostered this change. By using these sources, one could answer how the Mohawks became Christian, and what events led up to the incorporation of this religion in their tribe. They could also be used to look at the shift in culture in the Mohawk tribe, to see if the missionaries influence played a part in any new traditions the Mohawks adopted.

[1] Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, An account of some late attempts by the correspondents of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge to Christianize the North American Indians, (Edinburgh, 1763), 6.

[2] Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, 6.

[3] Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, 7.

[4] Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, 9.

[5] Cadwallader Colden, "The Character of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, by Lord Cadwallader Colden," in The Origin of the North American Indians: with a Faithful Description of Their Manners and Customs, Both Civil and Military, Their Religions, Languages, Dress, and Ornaments, New ed., ed. John McIntosh (New York, N: Nafis & Cornish, 1843), 301-303.

[6] Colden, " The Character of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, by Lord Cadwallader Colden," 304.

Works Cited

Cadwallader Colden, " The Character of the Five Indian Nations of Canada, by Lord Cadwallader Colden," in The Origin of the North American Indians: with a Faithful Description of Their Manners and Customs, Both Civil and Military, Their Religions, Languages, Dress, and Ornaments, New ed., ed. John McIntosh (New York, N: Nafis & Cornish, 1843), 301-307. < http://solomon.eena.alexanderstreet.com.libdata.lib.ua.edu/cgi-bin/asp/philo/eena/getpart.pl?S2995-D128>

Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge, An account of some late attempts by the correspondents of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge to Christianize the North American Indians (Edinburgh, 1763), <http://galenet.galegroup.com.libdata.lib.ua.edu/servlet/Sabin?af=RN&ae=CY105042216&srchtp=a&ste=14>

Read More

Violent Stereotype of the Apache by Chris Long

9/23/14

Violent Stereotype of the Apache

The Apache tribe is portrayed throughout history as a savage war-hungry people, who raided villages and tormented nearby groups. The fact is, the Apache raided for generations to protect their land from invasion. The Apache were actually have thought to wanted to stay peaceful, and were forced into the act of battle to remain a free people.[1] Although their want for peace might have been true, most European accounts of the Apache have portrayed them as violent. This stereotype of Apache has also lasted the test of time. Violent acts from the Apache are discussed in a letter from Juan de Oñate as early as 1599.

Juan de Oñate was eventually appointed the governor of New Mexico, but before that, he wrote this letter to the Spanish viceroy.[2] The letter was a description of his encounter with various peoples of the modern-day, southwest region of the United States. He mentions the Apache and describes them as a people who he has “compelled to render obedience to His Majesty.”[3] He discusses the Apache as a violent, out of line group who killed his maestro de campo.[4] Preceding the murder, Oñate decided to burn down their entire civilization, as a form of punishment for their actions. This sort of delinquent description is not exactly the same as the Apache are described in The Captivity of the Oatman Girls, written by Royal B. Stratton.

Stratton was author who wrote a book, based on a true story, about the kidnapping of two young girls by the Apache. The story says, Apache murdered the Oatman family; however they left Lorenzo Oatman to die, and spared the two youngest girls Olive, 13, and Mary Ann, 8. They forced the girls into hard labor, physical abuse and ridicule by the Apache children. The girls were then traded to the Mohave tribe for various goods, and their contact with the Apache finally came to an end. The Apache are described as evil for their alleged actions to the Oatman family. This sort of brutal, careless force is the main idea of the entire story, and is somewhat similar to what Oñate saw in the Apache tribe.[5]

The violence is a big part of the stereotype surrounding the Apache tribe, and is shown by both of these sources. Each story is told from the perspective of the Europeans, which is something to take into account. But both stories focus on the “savage natives”, and violent acts they committed on the Europeans; however, the violence comes into the story in separate ways.

The violence in the letter from Oñate seemed to be described as if the tribe could not take it any longer, and finally lashed out fatally and violently. This is not like the Royal B. Stratton story because, in the The Captivity of the Oatman Girls, the Apache viciously attacked an innocent family. Disobedience was not the cause for the violence, but instead a blood thirst for raiding and pillaging.

The Apache were not any more violent than any other group of people that was backed into a corner, but the connation of violence still follows the tribe when discussed in modern time. Europeans wrote both the sources discussed, so a bias more than likely presented itself. Thus in the eyes of the Europeans, the Apache were feared, violent people, and the idea has been accepted since the 16th century.

[1] Calloway (350)

[2] Ruler of country, higher authority

[3] Onate (23)

[4] Second in command, only to Onate

[5] Stratton, Royal B.

Works Cited

Calloway, Colin G. "Land Seizure and Removal to Reservations." In First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 350-352. Fourth ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Matin's, 2012.

Oñate, Juan De. "Oñate, Letter from New Mexico." 1599.

Stratton, R. B. Captivity of the Oatman Girls. New York: Pub. for the Author, by Carlton & Porter, 1858.

Downloadable version: Source_Analysis

Read MoreThe Lumbee Recognition Controversy by Caroline Barkley

THE LUMBEE RECOGNITION CONTROVERSY

The recognition of Native American tribes by the United States government is an issue that continues to be pressed upon congressional leaders in the twenty-first century. Legal definitions of what is considered “Indian” vary from state to state. This means that many people who identify themselves as members of a Native American tribe that are recognized by their state, may not be recognized by the United States federal government. This is important because federal recognition gives Native American tribes the right to establish tribal sovereignty amongst their people and allows their land to be protected by the federal government in land trusts. One of the most well-known tribes in the Southern United States struggling with this issue is the Lumbee Indian Tribe in North Carolina.

Throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, the Lumbee Indians have fought for federal recognition. In a 2002 article from the Seminole Tribune, Dean Chavers, a Lumbee Indian himself discusses the fight his people have been struggling to win. “A lot of Lumbees make their fight to be federally recognized the main part of their existence,” he states. Chavers believes that Indian people have to work together to achieve Indian rights. “We are in the same boat…” he writes, “…we have to make friends with other tribes, not be antagonistic…”. Chavers details how the opposition from other tribes was overwhelming when Lumbee leaders first began seeking help to reach federal recognition. At the NCAI meeting in 1972, he reports, that the Lumbees were extremely unprepared and received roughly two votes to terminate the Lumbee bill. Chavers explains that the Eastern-band of Cherokee Indians, primarily headed by Cherokee Principal Chief Jonathan Ed Taylor, has taken great strides to kill the Lumbee bill in Congress. He also states the irony of how Lumbee Indian tribe members have actually taken active steps in gaining and regaining recognition for other tribes, “only to have the leaders [of said] tribes turn on the Lumbees once they have their own recognition in hand”. In recent years, however, Chavers notes that many Indian leaders across the country have visited the Lumbee Indians located in Robeson County, North Carolina, to meet and gain firsthand knowledge of the tribe fighting for recognition. “Many have left with highly pro-Lumbee views” he says. He ends on a positive note, explaining that Lumbees must continue to fight for their rights as Native Americans and that recognition could soon be made possible for his people.

An Anthropologist consultant of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Dr. Jack Campsisi, gave testimony before the Committee on Indian Affairs of the United States Senate in 2006. His testimony for the Lumbee Indian tribe at this legislative hearing was documented. Dr.Campisi details how he conducted a vigorous study of the Lumbee Tribe from 1982 and 1988, spending more than twenty weeks in the community of the Lumbees in Robeson County. Campisi states that in his professional opinion, “the Lumbee Tribe exists as an Indian tribe and has done so over history.” He then gives his scholarly research on the tribal history of the Lumbee. He details the Civil War period when the Congress of 1830 passed Indian Removal legislation forcing all Indians regardless of tribe to leave North Carolina. Campisi notes that Lumbee Indians were also prohibited from serving in the Confederate Army after secession. Dr. Campisi then goes on to describe how the Lumbee Tribe gained state recognition and how they began seeking federal recognition starting in the late 19th century. All of these attempts failed, however. For instance, Campisi describes how several times the bill to accept the Lumbees as a federally recognized tribe would pass in the Senate but not in the House. In another case during the 1930s, the Lumbees were found to be “Indian” but the size of the Tribe and the costs of the government associated with recognition did not allow the bill to pass. Dr. Campisi next elaborates how the Lumbee meet the criterion for federal recognition. In the summary of his findings he explains that the Lumbee meets all the criteria for recognition and that there can be “no doubt about the Tribe’s ability to demonstrate [this] criteria.” He criticizes the Bureau of Indian Affairs, saying that their complaints of the Lumbee having “too little data” has no real evidence in dealing with this affair. Dr. Campisi ends stating that the record of the Lumbee Tribe’s history throughout the 18th , 19th and 20th centuries establish them as an Indian tribe defined by the Department of the Interior’s regulations and that “Congress can act on S.660 (the bill) with full confidence that the Lumbees are, in fact, an Indian tribe.”

These two documents are important to consider when researching the Lumbee Indian Recognition controversy because they give differing yet similar insight to the matter. Dean Chavers himself is aLumbee Indian. His article in a Native American newspaper carries a personal emotional tone. This gives the notion that this is a personal fight and issue for the Lumbee Tribe and that it is extremely important to them. Dr.Campisi’s documented testimony however, gives a scholarly and academic and even legal insight. Dr.Campisi uses extensive research and first-hand knowledge to address the issue of Lumbee federal recognition. He uses his academic findings to back up his opinion of allowing Lumbees to be federally recognized. By examining these texts, both an emotional personal response as well as an outside scholarly approach, one is able to comprehend the importance of this issue in Native American culture that spans from the nineteenth century into the twenty-first century. These primary sources could also provide questions for further investigation into the Lumbee Indian issue. One question to consider from the Chavers article; How has the Lumbee community responded as a whole rather than as a singular voice (i.e. Chaver’s opinion)? Also, is Chavers writing because he senses there may be a lack of fight behind the Lumbee tribe or is this simply a means for more press coverage of an issue he is personally passionate about? Matters to consider from Dr. Campisi’s testimony may suggest that his field studies should be extended; meaning, more data from this century should be collected to create a more precise argument for the Lumbee Indian’s recognition in 2014 and beyond.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Campsis, Jack. “Testimony before the Committee on Indian Affairs United States

Senate”, Legislative hearing on S.660, July 12 2006, http://www.indian.senate.gov/sites/default/files/upload/files/Campisi071206.pdf,accessed September 23 2014.

Chavers, Dean. “The Lumbee Controversy”, Seminole Tribune, July 05 2002,

http://search.proquest.com.libdata.lib.ua.edu/ethnicnewswatch/docview/362599353/BF9F1DA209D34D25PQ/9?accountid=14472, accessed September 23 2014

Boscana and Scholder by Sarah Banning

Geronimo Boscana and Fritz Scholder offer disparate views on the Luiseño tribe due to their vastly different time periods and backgrounds; however, Scholder relied on the retellings of his people’s stories and focused on the effects of the European perspective in his work. Not only did the stories and traditions of the Luiseño tribe influence the paintings of Fritz Scholder in style and content, but also the European and anti-Indian perspective offered by Friar Geronimo Boscana and other non-Indians in their retellings of the myths shaped Scholder’s conception of self and his artistic renderings of Indians.[1]

Friar Geronimo Boscana headed the St. Juan Capistrano Mission south of present day Los Angeles from 1812 till 1826, and he complied a mixture of his own writings on the native peoples and retellings of their stories.[2] Boscana wrote Chinigchinich in the hopes of supplying future friars with the knowledge necessary “to remove [the Indians’] erroneous belief, and give them an understanding of the true Religion.”[3] Boscana lays little stock in the faculties of the native peoples as he attempts to convert them to Christianity and discusses their stories and practices with a distinct air of condemnation and condescension.[4]

Fritz Scholder is considered one of the most prolific and influential Native American artists. He was a member of the Luiseño tribe, and though he denied his “Indianness” frequently his paintings illustrate a commitment to expanding the understanding of Indian art and Indian culture. His 1970 piece Mad Indian No. 3 is indicative of his usual style with a central harsh, humanoid figure- dressed in leggings, a loose tunic, and moccasin like shoes long hair- and some intrusion of an American flag, which in this case waves behind the solitary Indian figure.[5]

Fritz Scholder simultaneously grappled with the inextricable duality represented in Boscana’s text, the portrayal of Indian culture and custom intermingled with harsh and damning Eurocentric criticism, and both gave rise to Fritz’s art and are apparent in Angry Indian No. 3. Boscana consistently discussed the central figure of the chief, who across Boscana’s narrative was portrayed in similar terms of power, significance, and physical appearance, all of which were replicated in Scholder’s painting. Boscana described the power structure within the tribe as “toward [the chief] was observed but little respect.”[6] Boscana never makes any attempt to substantiate this statement, which merely reflects his inability to conceive of Indian culture and lifestyle outside of the context of his European values. Scholder engaged with this idea of the chief in Angry Indian No. 3, which depicts a screaming Indian with an American flag hovering over him.[7] This image elicits the ideas of the chief in Boscana’s work. The Indian in this work is dressed in regalia, holding a ritualistic instrument that implies his power, but does not assert it given that it is held low and loosely, just as Boscana had implied that all of the chief’s power was implied but not exercised due to lack of respect amongst the people. His anger weakens him and stems from the overpowering of himself and his people by American and European conquest. Here Scholder engaged with the usual narrative presented by Boscana where the weakness of Indians is internal, such as Europeans perceived Indians as unintelligent and barbaric since they lacked European values. This denied the reality of the devastation of Indians, which came from external forces, such as European invasion. In addition, Boscana described the flesh of the Indian gods and chiefs as being “painted black” for rituals and celebrations; however, Scholder chooses to instead paint his Indian in white with all other features save his hands being black and the only color being streaks of red in the American flag in the background.[8] Here Scholder disputed Boscana’s attempt to associate blackness with a negative idea of the Indian or savagery, and instead he paints the Indian white to associate the destruction of this man and his anger with whiteness or European and American colonization. This reasserts the chief as a respected being, not without fault or critique on Scholder’s part, but without quite the level of unexamined bias Boscana brings to his analysis of the systems of Indian life.

Though in some regards Scholder wished to dispute the traditional European image of the Indian, in some ways he engaged it as well, which highlighted the complexity of Indian life and Indian persons in a way that European negativity and romanticization did not achieve.[9] Boscana described the California Indians as “[consuming] [animal flesh] in a raw state.”[10] Scholder created this hyperbolic portrayal of a black-mouthed Indian with jagged teeth that simultaneously critiques Boscana’s dehumanization of Indians and the inaccurate romanticization of Indians in art. By not ignoring Boscana’s description, Scholder offers a more reliable critique since he hopes to create an image that encapsulates a myriad of views on the Indian. The Indian portrayed in Angry Indian No. 3 falls outside of the easy categorization of “savage” or “noble-savage.” Scholder merely wanted to portray Indians as he saw them, as complex, and in many cases angry and dismissed by a greater American culture, which is further illustrated by the elevation of the flag above the Indian in Scholder’s image. Furthermore, Scholder rebelled against Boscana’s patronizing bigotry by simultaneously accepting the oppressed state of Indians without the Indian he paints in this case being fully defeated. The Indians shoulders slouch slightly, but his anger and his indomitable form represents defiance to the flag behind him and to Boscana’s “amusement” towards Indians.[11] Scholder defies Boscana’s conception of a hapless Indian that can easily be manipulated to serve Boscana’s aims. Instead, Scholder offers a more holistic portrayal by playing off the dehumanization and comparison to animals offered by Boscana, and simultaneously he offers an emotive, powerful, and real Indian figure that defies the conventions of positive and negative portrayals, and the Indian becomes, as Scholder wanted him to be, a testament to human complexity.

Through drawing together Boscana’s Chinigchinich and Scholder’s Angry Indian No. 3, the staunchly unexamined bias of Boscana is thrown into sharp relief by the visual honesty of Scholder, and Boscana informs the subject matter of Scholder driving him to approach Indian art in a previously unsought way as Scholder attempted to dispel Boscana’s creation of the Indian chief as this powerless, ignored ruler, and corrupted ruler into a complex human who led their people but were subject to the difficulties of European invasion. Scholder sought through critique of Boscana’s dehumanization of Native peoples to create a holistic view of Indians that neither Boscana and other Europeans nor a romanticization of Indians provided.

[1]. Fritz Scholder is famous for denying that he is an Indian artist, which demonstrates his simultaneous internalized discomfort with the Indian and his unmanageable curiosity.

[2]. Boscana, Friar Geronimo, Chinigchinich, trans. Alfred Robinson (New York: Wiley and Putnam, 1846), vi-vii.

[5]. Fritz Scholder, Mad Indian No. 3, 1970, oil on Canvas, collection of Stéphane Janssen, Arizona.

[6]. Boscana, Chinigchinich, 2.

[7]. The image of the chief is common throughout Scholder’s paintings and many can be interpreted in a similar context using Boscana as Mad Indian No. 3.

[8]. Boscana, Chinigchinich, 7.

[9]. In my opinion, the painting that best illustrates this is Scholder’s 1969 piece Indian with Beer Can that seeks to confront the reality of alcoholism in the Indian community.

[10]. Boscana, Chinigchinich, 2.

Research Questions to Consider:

1. The wealth of Native produced art and European or Colonist produced art creates an interesting opportunity to compare and contrast between the two, and examine what drives particular biases and portrayals.

2. Scholder discussed throughout his life that since he was only one-fourth Native American that he could not claim the identity. Is the belief influenced by the national dialogue around tribal affiliation and recognition or from an internal struggle over his father's upbringing in a residential boarding school and his father going on to work for the Bureau of Indian Affairs?

Additional Resources

http://www.nmai.si.edu/exhibitions/scholder/

http://www.missionsjc.com/

Works Cited

Boscana, Geronimo. Chinigchinich, trans. Alfred Robinson. New York: Wiley and Putnam,

1846, vi-45. Accessed 10 Sept. 2014. <http://www.sacred-texts.com/nam/ca/bosc>

Scholder, Fritz. Mad Indian No. 3. 1970. Oil on Canvas. Collection of Stéphane Janssen,

Arizona. Accessed 18 Sept. 2014. <http://nmai.si.edu/exhibitions/scholder/works.html>

Read More

Creek Tribe by Caleb McCants

The tribe focused on in this paper is the Creek Indians. The primary sources chosen to discuss this tribe are a copy of a talk, between the Creek Chiefs and U.S. commissioners, and a copy of a set of laws of the Creek Nation of Indians. The talk is written by the U.S. commissioners, and is from their point of view, whereas the laws are written by the Creek Indians. The two sources discuss a similar topic from two opposite points of view. Both, however, give a very accurate depiction of the Creek Nation Tribe.

The first source, the talk, is in reply to the Creek Chiefs from U.S. Commissioners Duncan G. Campbell and James Meriwether on December 9, 1824. The Commissioners also include excerpts from President John Quincy Adams and Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. The authors’ point of view was obviously quite different than that of the Creek Indians. In fact, it was the opposite; however this source was very credible for the point of view it was depicting. This talk was a firsthand source of how the United States Government viewed Native Americans. The Commissioners looked down on the Creeks, and wanted them to change their way of life. In the talk, the Commissioners were informing the chiefs that their land belongs to the United States now. The talk begins with the Commissioners applauding the chiefs for being kind in their previous talk, although they expected nothing less “on account of the kindness and protection which has always been extended to you by the United States.”1 The Commissioners then go on to explain that whether they were pleased by it or not, at some point the Creek Nation had taken this land from someone else, and now it is being taken from them; or as they put it, “All the Country which was conquered, belonged then to the Conquerors.”2 The Commissioners also explained that their tribe, just like many others, had been treated like this because their forefathers fought on the side of the British in the Revolutionary War. However Adams now wanted to show mercy towards them, if they accept his terms, or he would “propose schemes for your injury or destruction.”3 Adams insisted that they move west and begin creating civilized laws, become good Christians and “free yourselves from barbarism.”4 This was a very typical view point of the United States. They viewed the Creeks as living poor lives, and wanted to improve their lifestyle by forcing them to become more “civilized” through laws and Christianity. They also discussed that they gave the same talk to the Cherokees and said they must do the same and they warned against the two tribes meeting and giving advice to one another. They went on to explain that a treaty had been signed with the Seminoles that they would be removed from their land and relocated. Essentially, the chiefs were being told their tribes must become more civilized, by creating a set of laws to follow and becoming Christians, and relocate and “By deciding for yourselves, it may prevent others from deciding for you.”5

The second source is a copy of law set by the Creek Nation of Indians on January 7, 1825 transcribed by Chilly McIntosh, a Creek leader and son of Chief William McIntosh. The laws also include the punishments associated with them if they are broken. The laws cover topics in depth such as murder, theft, past due debts, starting fires, marrying negro, livestock and not paying taxes. The punishments had a wide range from paying fines to death. The following is an example of the 39th law “And be it farther enacted if a man and wife should steal, while living together and after parted one Should tell on the other both Shall be punish as a thief.”6 These are laws the Creek Nation came up with and planned to live by. This source is from the point of view of the Creek Nation. It depicts the change in Creek culture as they become more “civilized”. While in the past this was not a typical document of the Creek’s, their lifestyle had been forced to change by the U.S. Government. This source is reliable in the fact that it was written by a Creek Indian, however the Creeks were forced into making these laws and therefor it is not an accurate depiction of their point of view.

These two sources relate to one another in that they both deal with Creek Nation of Indians’ laws. In the first source, the Creek Nation was being told they must start making and abiding by laws from the U.S. Government. In the second, they set out to make a list of laws and punishments to follow. The second document came almost exactly one month after the first. This could mean that the Creek Nation agreed to the terms the U.S. Commissioners set and made strides to becoming a more civilized nation, although they did not have much of a choice.

The two sources differ in the fact that they come from different authors. The first is a talk coming from the U.S. Commissioners to the chiefs of the Creek Nation whereas the second is a copy of laws set by the Creek Nation of Indians themselves. The second source seems to be a response in some way to the first. These sources could be used to analyze the relationship between the U.S. Government and the Creek Indians. The sources come from the viewpoint of both sides involved and how they interact with one another.

1. “[Talk] 1824 Dec. 9 to the [Creek] Chiefs / [delivered by] Duncan G. Campbell, James Meriwether, U.S. Comm[issione]rs” Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842: Accessed September 22, 2014. http://metis.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/tei-natamer-idx.pl?sessionid=c3c6ca82-0dae2f8a72-2075&type=doc&tei2id=TCC008

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. “Copy of laws of the Creek Nation, 1825 Jan. 7” Southeastern Native American Documents, 1730-1842: Accessed September 22, 2014. http://metis.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/tei-natamer-idx.pl?sessionid=c3c6ca82-0dae2f8a72-2075&type=doc&tei2id=KRC026

Bibliography

1. “Copy of laws of the Creek Nation, 1825 Jan. 7” January 7, 1825. http://metis.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/tei-natamer-idx.pl?sessionid=c3c6ca82-0dae2f8a72-2075&type=doc&tei2id=KRC026

2. “[Talk] 1824 Dec. 9 to the [Creek] Chiefs / [delivered by] Duncan G. Campbell, James Meriwether, U.S. Comm[issione]rs” December 9, 1824 http://metis.galib.uga.edu/ssp/cgi-bin/tei-natamer-idx.pl?sessionid=c3c6ca82-0dae2f8a72-2075&type=doc&tei2id=TCC008

Creek Nation by Tanika Powers

PRIMARY SOURCE ANALYSIS: CREEK NATION

The Creeks, also known as Muscogee, are Native people in the Southeastern part of the United States. They are not one tribe but a union of many several which was created by the many effects European invasion had on natives. Two primary sources are analyzed to show the Creek culture from the 19th and 20th century. Watercolors called “An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature at Mobile Alabama” from Edward Woolf and “Muskogee Polecat Dance” from Fred Beaver gives insight on how changes in America affected the Creeks culture and how the creators perceived them.

Woolf’s painting “An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature at Mobile Alabama” was created circa 1837. At first glance you see a figure foreground that is to be a Creek. The Creek looks to be covering their face as to shield with a blanket or clothing of some type from the viewer. It is not known of the figures gender but while looking at the figure it seems to be a male by the muscular legs. The figure’s shadow on the ground indicates that it is day time. Towards the middle ground to the right there is a tree behind a piece of high raised land. The tree looks to be dead because it is wilting. On the left side of the work, the grey color of the sky in the background creates a focal area. There is a tipi in the background which is to suggest being the Creeks’ home with more trees behind it. Under the image there is writing describing the content of the artwork.

Beaver’s painting “Muskogee Polecat Dance” was created in 1949. Muskogee Indians are in a big structure created out of logs around a fire. Eight men are dressed with feathers and bells with skunk skin on their backs dancing around the fire. Two natives sit on a rug in the foreground as three men stand on right and two men stand on left side at the background of the image. Some of the men not dancing create music with shakers too.

Both artists depicted Creek culture but they are opposite. Woolf who was an immigrate created more than one kind of art such as he worked with music while Beaver was a Native American artist. Woolf most likely interacted with the Creeks because the watercolor is sketched from nature as he indicated by writing so in the painting. Also the Creek appears to be approaching the viewer as to be approaching Woolf as he was creating the work.[1] Beaver’s image most likely shows true events because he was a Native American and so was surrounded by certain practices. Indications of first- hand knowledge are in the figures of the image with many details in their clothing and the dancing conveyed in the work has not just an ordinary stance of dance but particular crouching.[2]When it comes to Woolf’s watercolor there seems to be little or no bias. He painted the subject from real life and the colors used helps conveys that by using limited natural colors.[3] If the artwork had any influence of ideas such as stereotypes then the figure would have feathers, weapons and shown as a tall statured person like Europeans perceived Natives in images. Around 1837, the Second Creek War occurred when the government wanted to relocate Natives. Since Woolf’s work was created during that period it may show a time in history and that he wanted to record the outcome. How the figure gives off an insecure stance with their face covered gives in to the idea that the work recorded history because like many people who have been through tragedies they withdraw from others. Also with that in mind, for Woolf the Creeks are seen as naturally losers [4] Unlike Woolf, Beaver shows bias because since he is a Native the painting is more susceptible to show Creeks in a friendly and peaceful way even if it was not intentional. The Creeks are in a stereotypical way with how the men are dressed with feathers.[5] The painting was created in 1949; European influences with use of trade such as the use of horses, feathers, and beads etc. already affected Native cultures by then. With that in mind the paintings that Beaver created may depict history, show what have become of Creek culture and/ or since he was a Native gave a better understanding of where they come from.

The sources both depict the Creek life in different views. If the Creek in Mobile was painted in the aftermath of the war then this image would show how unstable life had become for the Creeks. Also the painting gives an insight of what kind of tribe they were at that moment. The tipi can indicate that the Creek migrated and that hunting was part of life with the skin needed to be used for the tipi.[6] Polecat dancing shows traditions and influence of other cultures that changed their lives when they incorporated new ideas into old ones. Beads and dyes for example from trade are integrated into ceremonial traditions such as the dance.[7] Woolf and Beaver equally convey their art in an exceptional way because the Creeks have real emotion and show actions natives have towards non- natives.

Creek culture and life are greatly depicted from both watercolor paintings. The sources would be used to give evidence to Creek culture and how Native and European interactions affected that. Images such as Woolf’s and Beaver’s can be helpful as evidence to history and many ways the European invaders affected Creek life.

[1]Edward Woolf. An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature of Mobile Alabama, c.1837. Watercolor painting. University Libraries Division of Special Collections: The University of Alabama.

[2]Fred Beaver. Muskogee Polecat Dancing, 1949. Watercolor painting. Philbrook Museum of Art. ArtStor. http://www.artstor.org/index.shtml.

[3] Woolf, An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature of Mobile Alabama.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Beaver, Muskogee Polecat Dancing.

[6] Woolf, An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature of Mobile Alabama.

[7] Beaver, Muskogee Polecat Dancing.

Bibliography

Fred Beaver, Muskogee Polecat Dancing, 1949. Watercolor painting. Philbrook Museum of Art. ArtStor. http://www.artstor.org/index.shtml.

Edward Woolf, An Indian of the Creek Nation Sketched from Nature of Mobile Alabama, c.1837. Watercolor painting. University Libraries Division of Special Collections: The University of Alabama.

Read MoreEuropean and Cherokee Affairs

by Lauren Morris

24 September 2014

European and Cherokee Affairs

Interactions between Native Americans and Europeans varied in different situations partly because the impressions made upon each other. The Cherokee tribe encountered the English in peaceful and non-peaceful meetings throughout trading, war, and various encounters. The “Letter from William Bull” and the “Letter from Alexander Garden,” contain both instances. The different encounters would have a prolonged affects for the Europeans and the Cherokees.

On July 8, 1762, Governor William Bull of Charleston, South Carolina wrote to Cadwallader Colden, Lieutenant Governor of New York to discuss a Chickasaw attack on the English. After defeating the Chickasaws, the English encountered the Cherokees who did not fire a shot nor inflict any harm which was not unexpected. [1] However, in the “Letter from Alexander Garden” written on October 26, 1760; a tale of the English burning many towns of the Cherokee tribes was told. These were their good towns used for living, trading, storing food and other uses, and had been burned in an act of warfare, in which the towns were completely destroyed. The Cherokees were allowed twenty-two days of peace by the English after their towns laid in ruins.[2] This letter shows the cruel warfare fought by English.

Both of the authors of the letters were noble English colonial officials. During the times of the events, the authors, Gov. William Bull and Alexander Garden, were reporting to the other leaders of the English and were merely reporting the events the army had encountered and told their hierarchal superiors. The validity of the authors’ writings could be correct. Knowing whether or not the authors were given the correct information by their informers, the individuals who participated in the encounters with the Cherokees, is incredibly difficult. The Europeans often stated tales of the New World being “untouched” while the Native American population totaled around one million people living across the continents of North and South America.[3]

A “Letter from William Bull” shows the Cherokee tribe choosing not to shoot at the English men, their rivals.[4] The Cherokee nation showed mercy on the enemies in the midst of their ongoing battles with the English. It is accurate to say that the Cherokee tribe did not want war with the colonists nor harm on the Cherokee nation. The author’s experience is typical in the sense that Native Americans did not want war in 1762, but perhaps wanted to fight the British in 1760. If the encounters between the Natives and the Europeans constituted of respect and without fear, the two populations could have co-existed. Respect for the English and Cherokee rituals by each group could have prospered a peaceful and beneficial relationship. A “Letter from Alexander Garden” shows the English’s brutal warfare tactics and fear towards the Cherokees and other Native nations. The English found difficulty in distinguishing between fierce and peaceful tribes.[5] However, in the times of war between the Cherokee nation and the English, peace was given for twenty two days in order for the Cherokee nation to re-coup after the tragedy experienced.[6] The author’s experience is both typical and exceptional. English were scared of a majority of the Native Americans and used terrible war tactics like burning villages and infecting Natives with small pox against Native Americans. However, the time of peace given to the Cherokee nation distinguished individuality.

The two sources establish the interactions and relationships between Native Americans like the Cherokees and the English throughout war. The Native Americans and Europeans had trouble communicating and understanding the different approaches to property, trading and hunting. The Cherokees were not fearful of war with the Europeans. The Europeans had encroached on their land, but the Native Americans were sometimes willing to share and coexist whereas the Europeans were not. The sources a “Letter from William Bull” and a “Letter from Alexander Garden” establish the fight for control of land and superiority. Interactions between the Native Americans and the Europeans vastly differed in experience, but similarities exist.

[1] William Bull, Letter to Cadwallader Colden, July 8, 1762, in the Letters an Papers of Cadwallader Colden, vol. 6, 1761-1764, ed. Lord Cadwallader Colden, Early Encounters in North America, Alexander Street Press, L.L.C., accessed September 23, 2014, http://solomon.eena.alexanderstreet.com/cgi-bin/asp/philo/eena/getpart.pl?S6966-D049.

[2] Alexander Garden, Letter to Cadwallader Colden, October 26, 1760, in Letters an Papers of Cadwallader Colden, vol. 5, 1755-1760, ed. Lord Cadwallader Colden, Early Encounters in North America, Alexander Street Press, L.L.C., accessed September 23, 2014, http://solomon.eena.alexanderstreet.com/cgi-bin/asp/philo/eena/getpart.pl?S6967-D177.

[3] Colin G. Galloway, First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 4th ed.(Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 6.

[4] William Bull, “Letter from William Bull”, 52

[5] Galloway, First Peoples 4th ed., 108

[6] Alexander Garden, “Letter from Alexander Garden”, 362

Bibliography

Bull, William. Letter to Cadwallader Colden. July 8, 1762. in Letters an Papers of Cadwallader Colden, vol. 6, 1761-1764. Ed. Lord Cadwallader Colden. Early Encounters in North America. Alexander Street Press, L.L.C. Accessed September 23, 2014. http://solomon.eena.alexanderstreet.com/cgi-bin/asp/philo/eena/getpart.pl?S6966- D049.

Galloway, Colin G. First Peoples: A Documentary Survey of American Indian History, 4th ed.(Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 6.

Garden, Alexander. Letter to Cadwallader Colden. October 26, 1760. in Letters an Papers of Cadwallader Colden, vol. 5 1755-1760. Ed. Lord Cadwallader Colden. Early Encounters in North America. Alexander Street Press, L.L.C. Accessed September 23, 2014. http://solomon.eena.alexanderstreet.com/cgi-bin/asp/philo/eena/getpart.pl?S6967-D177.

Read MoreAccounts of the Chickasaws

by Cade McCool

In this source analysis, the primary sources being analyzed portray the Chickasaw tribe. Document HP023 is a copy of a letter composed on September 29, 1795 by Chickasaw leader Opyomingo and was sent to General James Robertson, the United States Agent to the Chickasaw Nation, who was stationed in Nashville, TN.[1] Document HP022 is a letter composed on October 24, 1795 by General James Robertson to Colonel David Henley, an agent in the War Department who was stationed in Knoxville, TN.[2]

Opyomingo’s letter goes into great detail about a recent attack on his homeland by the neighboring Creek Indians, but his people were able to fight back and kill much more Creek warriors. He also requests that Gen. Robertson send white reinforcements and supplies to aid the Chickasaws and insists that he and Robertson be close allies. Gen. Robertson’s letter insinuates that the Creeks are dangerous and hypocritical, for they appear to seek peace but launch attacks on the Chickasaws. Also, he recounts of the very same attack by the Creeks on the Chickasaws that Opyomingo wrote about to him in the former letter about a month prior. It is easy to assume the Opyomingo’s first-person account of the attack is credible since he represents the Chickasaws and has very explicit and gruesome details. We are led to believe that he himself was in the actual attack. Overall, this makes his experience exceptional. Robertson appears to be restating the attack in his letter, so he may not be too reliable since he did not actually witness it. Therefore, his inexperience is typical.

Both documents prove that the Chickasaw Nation extended into the western half of Tennessee and also shows that the Creeks are based in Tennessee as well. Both imply that the Chickasaws are a majestic people who will retaliate when attacked. They both even admit that the Chickasaws are almost their own separate country since they are referred to as the Chickasaw Nation. Both also show that the Chickasaws were relentless enemies with the neighboring Creeks. However, Robertson’s letter acknowledges that the Chickasaws way of life is sustained by hunting seasons. His letter is biased, suggesting that the “Creeks have got a [complete] flogging as they well deserved” and that the Chickasaws did not deserve the surprise attack.[3] Opyomingo’s letter states that he and the Chickasaws are willing to be friends with the United States if they will assist them. Furthermore, Opyomingo’s letter emphasizes the fact that members of the Chickasaw nation would go to the aid of one another when needed, since the Chief guilt-trips Robertson by saying that “if you think [anything] of your Brothers you will Send one or two Hundred of your warriors to help your brothers hold to their Land”.[4]

[1] James Robertson. Letter to David Henley. October 24, 1795.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Opyomingo. Letter to James Robertson. September 29, 1795.

Bibliography

Opyomingo. Letter to General James Robertson. September 29, 1795.

Robertson, James. Letter to Colonel David Henley. October 24, 1795.

Read MoreCauses of the Nez Perce War

by Chandler Padgett

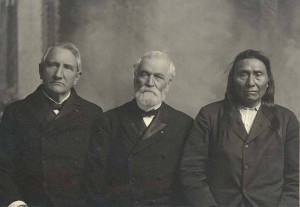

In the wake of the expansion of the US throughout the west, animosities flared between natives and settlers over land. The government attempted to resolve these disputes through treaties and the formation of reservations, though often the greed of settlers and dishonesty on the part of the government thwarted any chances at peace. A prime example of this is the case of the Nez Perce, who came into conflict with the US Army, known as the Nez Perce War, after a former treaty was broken by reducing their land.[1] Two accounts tell both the causes and happenings of the war itself, though they vary greatly in content. The writings, one by the Nez Perce Chief Joseph and the other by an Oregon-based suffragist Abigail Scott Duniway, mainly touch on three different causes: the settling of the land by whites, treaty disputes, and Indian attitudes.

It is a fact that the encroachment upon Nez Perce land by American settlers created the dispute in the first place, but the two sources differ in views about what role they played. Chief Joseph speaks rather extensively on the subject, saying that while they “thought there was enough room for all to live in peace,” the white men “were greedy to possess everything the Indian had.”[2] Despite the fact that he “labored hard to avoid trouble and bloodshed” and “gave up some of [his] country to the white men, thinking then that [he] could have peace,” the settlers “drove off a great many… cattle” and “would not let [them] alone.”[3] It could be said that he is biased, but he did not have much of a motive to cover up or mislead others about what happened as he had already been defeated two years prior. Therefore, his account gives great insight into the Nez Perce reaction to settlers and their defensive and originally peaceful stance regarding them, a reversal of Duniway, who portrayed the settlers as innocent—“the outbreak… is emphatically declared to be without the slightest provocation on the part of the settlers.” She is obviously biased in this claim, ignoring the wrongs perpetrated by them, likely blinded by her belief in Native American inferiority; this is depicted in her use of dehumanizing words like “savage” and “renegade.”[4] From these reports it is definite that the settlers had a role in starting the war, though whether the Indians did as well will be discussed later on.

The second factor of dispute between Americans and Nez Perce was the 1855 treaty and subsequent 1863 one that reduced the size of their land through American purchases, however shady. Duniway offers little insight into the actual discussions about land, but does reveal American opinions of the time. Ironically, in her newspaper advocating “free people,” she blames the war on “roving renegades” who refuse to “repair to the reservations designated by treaty.”[5] Chief Joseph’s account delves deeper into tricky situation that had evolved, saying that “a chief named Lawyer…sold nearly all the Nez Perce’s country” although “he had no right to sell the Wallowa country,”[6] showing that technically the US owned nothing, but due to their power and disregard of land rights, could use it as an excuse to apprehend others’ land. These two accounts illustrate why both sides believed to own the land and were angered to find others on it.

The final aspect of the conflict are the Nez Perce and their attitudes, and whether or not they instigated fights with American settlers. Duniway is quick to blame them, citing “a number of settlers” that “had been killed” and “an engagement” where “half of [Colonel Perry’s] command was killed.” Curiously enough, she adds that “this story may or may not be exaggerated,” implying that the “massacres” could have been fabricated as an excuse for war. Despite this possibility, she is nonetheless entrenched in her hatred of the natives, saying that “Indians will be true to their savage instincts,” even going so far as to recommend “extermination as the only safe and permanent treaty.”[7] Once again, Chief Joseph offers an enlightening perspective on the issue, pointing out that whites “reported many things that were false” in order to convince others that “we were going on the war path.”[8] Quite contrary to Duniway’s reports, he emphasizes repeatedly that he “did not want bloodshed”[9] and merely wanted to remain in “that beautiful valley of winding waters.” Finally, he reveals that a “young brave…whose father had been killed…had gone out…and killed four white men.” Although much less than claimed by Duniway, he was “deeply grieved” and “would have given [his] own life” to prevent it. He realizes that he was not representative of all Nez Perce however, saying “there were bad men among my people,” but defends them due to the fact that “they had been insulted a thousand times; their fathers and brothers had been killed; their mothers and wives disgraced.”[10] Despite recognizing his people’s wrongdoings, he implies that they had no other avenues to take under such pressure.

In conclusion, there seems to be ample blame on each side, which raises Chief Joseph’s question-- “who was first to blame?”[11] Duniway would suggest the Nez Perce with their “threatening attitude”[12] towards innocent settlers, while Chief Joseph blames the aggressive whites and their harsh treatments of Indians mentioned above; based on the fact that Americans were the aggressors and Indians were merely reacting, it seems that the latter opinion is the correct one. Here an important distinction can be made; while Joseph realizes that there are “good white friends,”[13] Duniway generalizes the whole race of “redskins” as “savages,” [14] which is telling of many American views of the period. This distinction reveals more things about the authors themselves; while Duniway is a suffragist merely writing her opinion about news of the time, Joseph lived and experienced the war first-hand, therefore lending him much more credibility. Furthermore, if one was to use such sources in a more intensive research project, Duniway’s would be helpful to offer insight about white prejudices of the period, while Chief Joseph’s would significantly aid in understanding native opinions, beliefs, and struggles in the face of American power.

Bibliography

Duniway, Abigail. "Indian Outbreak in Idaho." The New Northwest (Portland), June 22, 1877, accessed September 23, 2014, http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/

Duniway, Abigail. "The Indian War in Idaho." The New Northwest (Portland), June 29, 1877, accessed September 23, 2014, http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/

Joseph, Chief. "An Indian's View of Indian Affairs." The North American Review 128, no. 269 (1879): 412-434.

[1] Chief Joseph, "An Indian's View of Indian Affairs," The North American Review 128, no. 269 (1879): 412-434, accessed September 23, 2014, http://digital.library.cornell.edu/.

[2] Ibid., 416.

[3] Ibid., 419.

[4] Abigail Duniway, "The Indian War in Idaho," The New Northwest, June 29, 1877, accessed September 23, 2014, http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/.

[5] Duniway, “Indian Outbreak”, 2.

[6] Joseph, “Indian’s View”, 417.

[7] Abigail Duniway, "Indian Outbreak in Idaho," The New Northwest, June 22, 1877, accessed September 23, 2014, http://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/.

[8] Joseph, “Indian’s View”, 418.

[9] Ibid., 423.

[10] Ibid., 424.

[11] Ibid., 424.

[12] Duniway,” Indian Outbreak”, 2.

[13] Joseph, “Indian’s View”, 424.

[14] Duniway, “Indian War”, 2.

Read MoreApache Buffalo Hunt

by Coleman Gothard

Have you ever wondered what the Great Plains looked like 200 years ago? Nebraska, Oklahoma, Montana, Wyoming, Kansas, and the Dakotas these territories are all contributors to what was once called the Great Plains. The Great Plains played host to numerous tribes such as the Blackfoot, Sioux, Lakota, apache, crow, and Chichimec peoples. These native tribes thrived on the Great Plains due to several contributing factors. The biggest of these factors is the buffalo it was the main food staple of the plains Indians.

Most people view these plains Indians as chasing down buffalo on horseback. “Nowhere did Indians wear headdresses and hunt buffalo from horse back; the horse-and-buffalo culture of the plains Indians developed much later, a by-product of contact with Europeans”[1]. So just how important was the buffalo to the tribes of the Great Plains, the buffalo was everything. When the buffalo struggled the plains tribes struggled as well. The buffalo is not only the main staple of the plains but is responsible for famine, freezing tribes, and the instigator of many wars: as stated by Calloway (2012) “ the buffalo made the great plains an arena of competition between rival tribes jostling for position of rich hunting grounds.”2

Buffalo were central in the lives of plains Indians, but tribes such as the dakota and crow only began to hunt on horse back in the second half of eighteenth . When analyzing these strategies art paintings of the apache buffalo hunt, and Kiowa ledger art will be analyzed. The apache buffalo hunt painting is authored by George Catlin in 1837, it is titled “Buffalo Hunt under the Wolf-skin Mask.”3 Depicted in this painting are 2 apaches stalking a herd of buffalo wearing nothing but a wolf pelt draped over them and armed with a bow and arrow. Buffalo hunts had to be coordinated to be successful, and a successful hunt was no easy task. Buffalo were very dangerous, and when hunted on foot native were in danger of serious injury.

http://www.cartermuseum.org/Inspiring_Visions/Catlin/catlin.html

In Catlin’s painting it appears that Catlin is from a distance while creating this particular work. This work truly shows the importance of the buffalo to not only the apache peoples but to the entire plains tribes. The two apache hunter are putting their lives on the line to feed their family with the most dangerous but abundant food source in the area. If the buffalo decided to charge the results would be devastating, and could easily lead to death for the two hunters. Catlin is a well-respected artist of the 19th century, and his work really emphasizes the depth and importance of the Native American traditions.

Catlin in my opinion portrayed the plains Indians as accurately as possible. The time and experiences he had with the tribes really opened the doors for Native American understanding. His artwork so pinpoint, so vivid such as the work portrayed in this writing. The way the buffalo and the natives are depicted it is like they are drawn to one another, but it goes further than that in the mutual understanding of you help me and I will help you. It dives into the heart and soul of the viewer and you feel the respect and the dependence that the native and the buffalo have for one another.

The next source observed is called a Kiowa ledger painting “Kiowa Buffalo Hunt.”4 This painting compared to Catlin’s is no comparison; the art really does not capture the attention of the viewer as Catlin’s work does. Even with the dull flat ledger art, it is still powerful symbolism, and if studied correctly poses a great understanding to the importance of the horse and buffalo. Though this is Kiowa art both apache and Kiowa used the horse to hunt buffalo. The hunting styles on horseback would be so similar that a difference would be hard to pick out.

The introduction of the horse was the start of a revolution on the Great Plains. Calloway (2012) said “horses transformed plains Indians into mobile communities, capable of traveling great distances and fully exploiting the rich resources of their environment”(p.182). This means that Great Plains tribes could now move greater distances faster, expand trade networks, and hunt more efficiently. Now with the introduction of the horse the buffalo hunt went from a stalk hunt to a run down and slaughter. With the introduction of the horse the apaches can now kill more food, and support larger communities at half the energy expense.

As depicted in the Kiowa ledger art one hunter is taking down one buffalo, oppose to the two apaches in Catlin’s photo focusing on one takedown. The Kiowa hunter is right alongside the buffalo and has just thrusted a spear into its side. Now all the hunter has to do is ride alongside the buffalo till it falls instead of having to track it one foot. “Lives were much harder on the plains before the horse, and life is much easier with the horse on the Plains.”5

The Kiowa painting is flat and dull as opposed to Catlin’s work, but do not discredit what the work says. It is depicting the advancement of a long time primitive society that lived long and hard without the new technologies of this world. Considering half the world away had horses for thousands of years and at times barely survived. Native Americans have had them for a mere 300 years and thrived. Even with the thriving Great Plain civilization, both of these painting depict the importance of the buffalo. With the advances in Great Plains cultures such as steel, guns, and horses, the buffalo was still the most important key for survival on the Great Plains.

Notes

[1] Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples A Documentary Survey of American Indian History

(Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 25.

2 Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples A Documentary Survey of American Indian History

(Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 183.

3 George Catlin, “Buffalo Hunt under the Wolf-skin Mask.” C.M. Russell Museum. 1833 https://www.cmrussell.org/temporary-exhibitions

4 Charles Emerson Rowell, “Kiowa Buffalo Hunt.” Boston Avenue Frame. 1909.

http://bostonavenueframetheavenuestudio.com/nativeamericanssorted.html

5 Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples A Documentary Survey of American Indian History

(Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 183.

Bibliography

- Colin G. Calloway, First Peoples A Documentary Survey of American Indian History

(Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2012), 25,182, 183.

- Charles Emerson Rowell, “Kiowa Buffalo Hunt.” Boston Avenue Frame. http://bostonavenueframetheavenuestudio.com/nativeamericanssorted.html

- George Catlin, “Buffalo Hunt under the Wolf-skin Mask.” M. Russell Museum. 1833. https://www.cmrussell.org/temporary-exhibitions

Montgomery

Montgomery /mɒntˈɡʌməri/ is the capital of the State of Alabama, and is the county seat of Montgomery County.[5] Named for Richard Montgomery, it is located on the Alabama River, in the Gulf Coastal Plain.

Read More